Yvon Grenier From Art to Politics Octavio Paz and the Pursuit of Freedom Pdf Online

| Octavio Paz | |

|---|---|

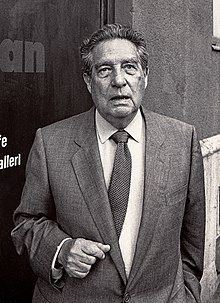

Paz in 1988 | |

| Built-in | Octavio Paz Lozano (1914-03-31)March 31, 1914 Mexico Urban center, Mexico |

| Died | April 19, 1998(1998-04-nineteen) (anile 84) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1931–1965 |

| Literary movement |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Elena Garro |

Octavio Paz Lozano [a] (March 31, 1914 – April 19, 1998) was a Mexican poet and diplomat. For his trunk of piece of work, he was awarded the 1977 Jerusalem Prize, the 1981 Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the 1982 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Early life [edit]

Octavio Paz was born about Mexico City. His family was a prominent political family in Mexico,[1] with Spanish and indigenous Mexican roots.[2] His father had been an assistant to Emiliano Zapata. The family experienced financial ruin afterwards the Mexican Revolution and the exile of Zapata supporters (known every bit Zapatistas). The family briefly relocated to Los Angeles before returning to Mexico.[1]

Paz was introduced to literature early in his life through the influence of his grandfather's library, filled with archetype Mexican and European literature.[3] During the 1920s, he discovered Gerardo Diego, Juan Ramón Jiménez, and Antonio Machado. These Spanish writers had a slap-up influence on his early writings.[4]

As a teenager in 1931, Paz published his first poems, including "Cabellera". Ii years afterwards, at the age of nineteen, he published Luna Silvestre ("Wild Moon"), a collection of poems. In 1932, with some friends, he funded his beginning literary review, Barandal.

For a few years, Paz studied police force and literature at National University of Mexico.[two] During this fourth dimension, he became familiar with leftist poets, such every bit Pablo Neruda.[ane] In 1936, Paz abased his law studies and left Mexico City for Yucatán to work at a school in Mérida. The school was set up for the sons of peasants and workers.[5] [6] There, he began working on the first of his long, ambitious poems, "Entre la piedra y la flor" ("Between the Rock and the Flower") (1941, revised in 1976). Influenced by the piece of work of T. South. Eliot, it explores the situation of the Mexican peasant under the domineering landlords of the solar day.[7]

In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the state of war in Spain, held in Valencia, Barcelona and Madrid and attended past many writers including André Malraux, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender and Pablo Neruda.[viii] Paz showed his solidarity with the Republican side and against fascism. He also visited Paris while in Europe. There, he encountered the surrealist movement, which left a profound bear on upon him.[9] After his return to Mexico, Paz co-funded a literary journal, Taller ("Workshop") in 1938, and wrote for the magazine until 1941. In 1937 he married Elena Garro, who is considered ane of Mexico'south finest writers. They had met in 1935. They had i daughter, Helena, and were divorced in 1959.

In 1943, Paz received a Guggenheim Fellowship and used it to report at the University of California at Berkeley in the United States. Ii years afterward he entered the Mexican diplomatic service, and was assigned for a fourth dimension to New York City. In 1945, he was sent to Paris, where he wrote El Laberinto de la Soledad ("The Labyrinth of Solitude"). The New York Times subsequently described it as "an analysis of modern United mexican states and the Mexican personality in which he described his young man countrymen as instinctive nihilists who hide backside masks of confinement and ceremoniousness."[x] In 1952, he travelled to India for the starting time time. That same yr, he went to Tokyo, as chargé d'affaires. He adjacent was assigned to Geneva, Switzerland. He returned to Mexico Metropolis in 1954, where he wrote his great verse form "Piedra de sol" ("Sunstone") in 1957, and published Libertad bajo palabra (Liberty under Oath), a compilation of his poetry upward to that fourth dimension. He was sent over again to Paris in 1959. In 1962, he was named Mexico'south ambassador to India.

After life [edit]

In New Delhi, as Ambassador of Mexico to India, Paz completed several works, including El mono gramático (The Monkey Grammarian) and Ladera este (Eastern Slope). While in Bharat, he met numerous writers of a grouping known as the Hungry Generation and had a profound influence on them.

In 1965, he married Marie-José Tramini, a French woman who would be his wife for the rest of his life. That fall in 1965 he went to Cornell and taught two courses, one in Spanish and one in English. The magazine LIFE en Español published a piece nearly his stay at Cornell in their July 4, 1966 issue. There are several pictures in the article. After this he returned to Mexico. In 1968, he resigned from the diplomatic service in protest of the Mexican government'south massacre of student demonstrators in Tlatelolco.[xi] Subsequently staying in Paris for refuge, he returned to Mexico in 1969. He founded his magazine Plural (1970–1976) with a group of liberal Mexican and Latin American writers.

From 1969 to 1970 he was Simón Bolívar Professor at Cambridge University. He was as well a visiting lecturer during the tardily 1960s and the A. D. White Professor-at-Large from 1972 to 1974 at Cornell University. In 1974 he lectured at Harvard University as Charles Eliot Norton Lecturer. His volume Los hijos del limo ("Children of the Mire") was the outcome of those lectures. After the Mexican authorities airtight Plural in 1975, Paz founded Vuelta, some other cultural magazine. He was editor of that until his expiry in 1998, when the magazine closed.

He won the 1977 Jerusalem Prize for literature on the theme of private liberty. In 1980, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Harvard, and in 1982, he won the Neustadt Prize. In one case proficient friends with novelist Carlos Fuentes, Paz became estranged from him in the 1980s in a disagreement over the Sandinistas, whom Paz opposed and Fuentes supported.[12] In 1988, Paz's magazine Vuelta published criticism of Fuentes past Enrique Krauze, resulting in estrangement between Paz and Fuentes, who had long been friends.[13]

A collection of Paz's poems (written betwixt 1957 and 1987) was published in 1990. In 1990, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.[14]

He died of cancer on April nineteen, 1998, in Mexico City.[15] [16] [17]

Guillermo Sheridan, who was named by Paz as director of the Octavio Paz Foundation in 1998, published a volume, Poeta con paisaje (2004) with several biographical essays about the poet's life upwards to 1998, when he died.

Aesthetics [edit]

"The poetry of Octavio Paz", wrote the critic Ramón Xirau, "does non hesitate between linguistic communication and silence; it leads into the realm of silence where true language lives."[eighteen]

Writings [edit]

A prolific author and poet, Paz published scores of works during his lifetime, many of which take been translated into other languages. His poetry has been translated into English by Samuel Beckett, Charles Tomlinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Muriel Rukeyser and Mark Strand. His early on poesy was influenced past Marxism, surrealism, and existentialism, as well equally religions such every bit Buddhism and Hinduism. His poem, "Piedra de sol" ("Sunstone"), written in 1957, was praised equally a "magnificent" example of surrealist poetry in the presentation speech of his Nobel Prize.

His later poesy dealt with beloved and eroticism, the nature of time, and Buddhism. He also wrote poetry most his other passion, modern painting, dedicating poems to the work of Balthus, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Antoni Tàpies, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roberto Matta. As an essayist Paz wrote on topics such every bit Mexican politics and economics, Aztec art, anthropology, and sexuality. His book-length essay, The Labyrinth of Solitude (Spanish: El laberinto de la soledad), delves into the minds of his countrymen, describing them as subconscious behind masks of solitude. Due to their history, their identity is lost between a pre-Columbian and a Spanish culture, negating either. A key piece of work in understanding Mexican culture, it profoundly influenced other Mexican writers, such as Carlos Fuentes. Ilan Stavans wrote that he was "the quintessential surveyor, a Dante's Virgil, a Renaissance homo".[19]

Paz wrote the play La hija de Rappaccini in 1956. The plot centers around a young Italian student who wanders about Professor Rappaccini's beautiful gardens where he spies the professor'southward girl Beatrice. He is horrified to notice the poisonous nature of the garden's dazzler. Paz adapted the play from an 1844 curt story by American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, which was also entitled "Rappaccini's Daughter". He combined Hawthorne's story with sources from the Indian poet Vishakadatta and influences from Japanese Noh theatre, Spanish autos sacramentales, and the poetry of William Butler Yeats. The play'due south opening functioning was designed by the Mexican painter Leonora Carrington. In 1972, Surrealist author André Pieyre de Mandiargues translated the play into French equally La fille de Rappaccini (Editions Mercure de France). Outset performed in English in 1996 at the Gate Theatre in London, the play was translated and directed by Sebastian Doggart and starred Sarah Alexander as Beatrice. The Mexican composer Daniel Catán adjusted the play as an opera in 1992.

Paz's other works translated into English include several volumes of essays, some of the more prominent of which are Alternate Electric current (tr. 1973), Configurations (tr. 1971), in the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works,[20] The Labyrinth of Solitude (tr. 1963), The Other United mexican states (tr. 1972); and El Arco y la Lira (1956; tr. The Bow and the Lyre, 1973). In the United States, Helen Lane'southward translation of Alternate Current won a National Book Honor.[21] Along with these are volumes of critical studies and biographies, including of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Marcel Duchamp (both, tr. 1970), and The Traps of Faith, an analytical biography of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the Mexican 17th-century nun, feminist poet, mathematician, and thinker.

His works include the verse collections ¿Águila o sol? (1951), La Estación Violenta, (1956), Piedra de Sol (1957). In English, Early Poems: 1935–1955 (tr. 1974) and Nerveless Poems, 1957–1987 (1987) have been edited and translated past Eliot Weinberger, who is Paz'southward principal translator into American English.

Political thought [edit]

Ii International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture.

Originally, Paz supported the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, merely after learning of the murder of one of his friends by the Stalinist secret police, he became gradually disillusioned. While in Paris in the early 1950s, influenced by David Rousset, André Breton and Albert Camus, he started publishing his critical views on totalitarianism in general, and particularly against Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union.

In his magazines Plural and Vuelta, Paz exposed the violations of human rights in communist regimes, including Castro's Cuba. This brought him much animosity from sectors of the Latin American left. In the prologue to Volume Ix of his complete works, Paz stated that from the fourth dimension when he abandoned communist dogma, the mistrust of many in the Mexican intelligentsia started to transform into an intense and open enmity. Paz connected to consider himself a man of the left, the democratic, "liberal" left, not the dogmatic and illiberal i. He also criticized the Mexican government and leading political party that dominated the nation for most of the 20th century.

Politically, Paz was a social democrat, who became increasingly supportive of liberal ideas without ever renouncing to his initial leftist and romantic views. In fact, Paz was "very slippery for anyone thinking in rigid ideological categories," Yvon Grenier wrote in his book on Paz's political thought. "Paz was simultaneously a romantic who spurned materialism and reason, a liberal who championed freedom and republic, a bourgeois who respected tradition, and a socialist who lamented the withering of fraternity and equality. An advocate of fundamental transformation in the fashion nosotros run into ourselves and modernistic gild, Paz was also a promoter of incremental alter, not revolution."[22]

In that location can be no club without poetry, but society can never be realized every bit poetry, it is never poetic. Sometimes the two terms seek to interruption apart. They cannot.

—Octavio Paz[23]

In 1990, during the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin wall, Paz and his Vuelta colleagues invited several of the world's writers and intellectuals to United mexican states City to discuss the collapse of communism. Writers included Czesław Miłosz, Hugh Thomas, Daniel Bell, Ágnes Heller, Cornelius Castoriadis, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Jean-François Revel, Michael Ignatieff, Mario Vargas Llosa, Jorge Edwards and Carlos Franqui. The encounter was chosen The feel of freedom (Spanish: La experiencia de la libertad) and broadcast on Mexican television from 27 August to ii September.[24]

Paz criticized the Zapatista uprising in 1994.[25] He spoke broadly in favor of a "military machine solution" to the insurgence of January 1994, and hoped that the "army would soon restore order in the region". With respect to President Zedillo's offensive in February 1995, he signed an open up letter of the alphabet that described the offensive every bit a "legitimate government action" to reestablish the "sovereignty of the nation" and to bring "Chiapas peace and Mexicans tranquility".[26]

First literary experiences [edit]

Paz was dazzled by The Waste Land past T. S. Eliot, in Enrique Munguia's translation every bit El Páramo which was published in the magazine Contemporaries in 1930. As a result of this, although he maintained his main interest in poetry, he had an unavoidable outlook on prose: "Literally, this dual practise was for me a game of reflections between verse and prose".

Worried about confirming the being of a link between morals and poetry, in 1931, at the age of 16, he wrote what would be his commencement published article, "Ethics of the Creative person", where he planted the question about the duty of an artist among what would be deemed art of thesis, or pure art, which disqualifies the second as a result of the teaching of tradition. Assimilating a language that resembles a religious style and, paradoxically, a Marxist way, finds the true value of art in its purpose and pregnant, for which, the followers of pure art, of which he's not one, are establish in an isolated position and favor the Kantian thought of the "man that loses all relation with the world".[27]

The mag Barandal appeared in Baronial 1931, put together past Rafael López Malo, Salvador Toscano, Arnulfo Martínez Lavalle and Octavio Paz. All of them were not nevertheless in their youth except for Salvador Toscano, who was a renowned writer thanks to his parents. Rafael López participated in the magazine, "Mod" and, too as Miguel D. Martínez Rendón, in the movimiento de los agoristas, although it was more commented on and known past the high school students, over all for his poem, "The Golden Beast". Octavio Paz Solórzano became known in his circumvolve as the occasional author of literary narratives that appeared in the Sunday newspaper add-in El Universal, too as Ireneo Paz which was the name that gave a street in Mixcoac identity.

Awards [edit]

- Inducted Fellow member of Colegio Nacional, Mexican highly selective university of arts and sciences 1967[28]

- Peace Prize of the German language Book Trade

- National Prize for Arts and Sciences (Mexico) in Literature 1977

- Honorary Doctorate National Autonomous University of United mexican states 1978[29]

- Honorary Doctorate (Harvard University) 1980[30]

- Ollin Yoliztli Prize 1980

- Miguel de Cervantes Prize 1981

- Nobel Literature Prize in 1990[14]

- Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian republic 1991[31]

- Premio Mondello (Palermo, Italian republic)

- Alfonso Reyes International Prize

- Neustadt International Prize for Literature 1982

- Jerusalem Prize

- Menéndez Pelayo International Prize

- Alexis de Tocqueville Prize

- Xavier Villaurrutia Award

Listing of works [edit]

Poetry collections [edit]

- 1933: Luna silvestre

- 1936: No pasarán!

- 1937: Raíz del hombre

- 1937: Bajo tu clara sombra y otros poemas sobre España

- 1941: Entre la piedra y la flor

- 1942: A la orilla del mundo, compilation

- 1949: Libertad bajo palabra

- 1950: El laberinto de la soledad

- 1954: Semillas para un himno

- 1957: Piedra de Sol (Sunstone)

- 1958: La estación violenta

- 1962: Salamandra (1958–1961)

- 1965: Viento entero

- 1967: Blanco

- 1968: Discos visuales

- 1969: Ladera Este (1962–1968)

- 1969: La centena (1935–1968)

- 1971: Topoemas

- 1972: Renga: A Chain of Poems with Jacques Roubaud, Edoardo Sanguineti and Charles Tomlinson

- 1974: El mono gramático

- 1975: Pasado en claro

- 1976: Vuelta

- 1979: Hijos del aire/Airborn with Charles Tomlinson

- 1979: Poemas (1935–1975)

- 1985: Prueba del nueve

- 1987: Árbol adentro (1976–1987)

- 1989: El fuego de cada día, option, preface and notes past Paz

Anthology [edit]

- 1966: Poesía en movimiento (México: 1915–1966), edition by Octavio Paz, Alí Chumacero, Homero Aridjis and Jose Emilio Pacheco

Essays and Assay [edit]

- 1993: La Llama Doble, Amor y Erotismo

Translations by Octavio Paz [edit]

- 1957: Sendas de Oku, by Matsuo Bashō, translated in collaboration with Eikichi Hayashiya

- 1962: Antología, by Fernando Pessoa

- 1974: Versiones y diversiones (Collection of his translations of a number of authors into Spanish)

Translations of his works [edit]

- 1952: Anthologie de la poésie mexicaine, edition and introduction by Octavio Paz; translated into French by Guy Lévis-Mano

- 1958: Anthology of Mexican Poetry, edition and introduction by Octavio Paz; translated into English by Samuel Beckett

- 1971: Configurations, translated by G. Aroul (and others)

- 1974: The Monkey Grammarian (El mono gramático); translated into English by Helen Lane)

- 1995: The Double Flame (La Llama Double, Amor y Erotismo); translated by Helen Lane

Notes [edit]

- ^ Castilian pronunciation: [okˈtaβjo pas loˈsano],

sound(aid·info) .

sound(aid·info) .

- Hernández, Consuelo. "The Poetry of Octavio Paz". Library of Congress, 2008. https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-4329/

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Foundation, Verse (2020-06-07). "Octavio Paz". Poesy Foundation . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

- ^ a b Poets, Academy of American. "Virtually Octavio Paz | Academy of American Poets". poets.org . Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

- ^ Guillermo Sheridan: Poeta con paisaje: ensayos sobre la vida de Octavio Paz. México: ERA, 2004. p. 27. ISBN 968411575X

- ^ Jaime Perales Contreras: "Octavio Paz y el circulo de la revista Vuelta". Ann Arbor, Michigan: Proquest, 2007. pp.46–47. UMI Number 3256542

- ^ Sheridan: Poeta con paisaje, p. 163

- ^ Quiroga, Jose; Hardin, James (1999). Understanding Octavio Paz. Univ of Southward Carolina Press. ISBN978-i-57003-263-9.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (1986). Octavio Paz. Boston: K. K. Hall.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2012). The Spanish Ceremonious War (50th Anniversary ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 678. ISBN978-0-141-01161-5.

- ^ Riding, Alan (1994-06-11). "Octavio Paz Goes Looking for His Old Friend Eros". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-06-07 .

- ^ Rule, Sheila (October 12, 1990). "Octavio Paz, Mexican Poet, Wins Nobel Prize". New York Times. New York.

- ^ Preface to The Collected Poems of Octavio Paz: 1957–1987 by Eliot Weignberger

- ^ Anthony DePalma (May fifteen, 2012). "Carlos Fuentes, Mexican Man of Messages, Dies at 83". The New York Times . Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Marcela Valdes (May 16, 2012). "Carlos Fuentes, Mexican novelist, dies at 83". The Washington Post . Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Octavio Paz on Nobelprize.org , accessed 29 April 2020

- ^ México, Distrito Federal, Registro Civil (twenty Apr 1998). "Civil Death Registration". FamilySearch.org. Genealogical Society of Utah. 2002. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arana-Ward, Marie (1998). "Octavio Paz, Mexico'due south Bully Idea Human being". The Washington Post . Retrieved October three, 2013.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (1998). "Octavio Paz, United mexican states'southward Man of Letters, Dies at 84". New York Times . Retrieved Oct 3, 2013.

- ^ Xirau, Ramón (2004) Entre La Poesia y El Conocimiento: Antologia de Ensayos Criticos Sobre Poetas y Poesia Iberoamericanos. United mexican states City: Fondo de Cultura Económica p. 219.

- ^ Stavans (2003). Octavio Paz: A Meditation. University of Arizona Printing. p. 3.

- ^ Configurations, Historical Collection: UNESCO Culture Sector, UNESCO official website

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1974". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-eleven.

At that place was a National Book Award category Translation from 1967 to 1983. - ^ Yvon Grenier, From Art to Politics: Octavio Paz and the Pursuit of Freedom (Rowman and Littlefield, 1991); Castilian trans. Del arte a la política, Octavio Paz y la busquedad de la libertad (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1994).

- ^ Paz, Octavio. "Signs in Rotation" (1967), The Bow and the Lyre, trans. Ruth Fifty.C. Simms (Austin: University of Texas Printing, 1973), p. 249.

- ^ Christopher Domínguez Michael (November 2009). "Memorias del encuentro: "La experiencia de la libertad"". Letras Libres (in Spanish) . Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Huffschmid (2004) pp127-151

- ^ Huffschmid (2004) p145

- ^ Paz, Octavio (1988). Primeras letras (1931–1943). Vuelta. p. 114.

- ^ Member of Colegio Nacional (in spanish) Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Car

- ^ "Honorary Degree National Autonomous University of Mexico". Archived from the original on 2014-02-25.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Harvard University".

- ^ Presidency of the Italian Commonwealth. "Awards granted to Octavio Paz by the Italy" (in Italian). Retrieved Baronial 13, 2013.

External links [edit]

- Zona Octavio Paz

- Nobel museum biography and list of works

- Boletin Octavio Paz

- "Octavio Paz" The Art of Poetry No. 42 Summer 1991 The Paris Review

- Octavio Paz on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1990 In Search of the Present

- Recorded in Washington D.C. on October 18, 1988. Video (1 Hour)

- Petri Liukkonen. "Octavio Paz". Books and Writers

- Consuelo Hernández, Enrico Santí on Octavio Paz. Recorded at the Library of Congress for the Hispanic Division's video literary archive. 2005

- Review of Octavio Paz: El poeta y la revolución, Enrique Krauze, Mexican Studies/Estudios mexicanos (2015), 31 (1): 196–200.

- Octavio Paz Corral recorded at the Library of Congress for the Hispanic Segmentation's audio literary archive on March 23-24, 1961

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octavio_Paz

0 Response to "Yvon Grenier From Art to Politics Octavio Paz and the Pursuit of Freedom Pdf Online"

Post a Comment